Ike Sturm

Songs are born when we listen to the Spirit of God moving within and around us. I serve as music director for the Jazz Ministry at Saint Peter’s Church in New York City. Our jazz liturgies, at 5 p.m. on Sunday, began in 1965 and provide fertile ground for cultivating innovative sounds and song-leading techniques. I am extremely blessed to have a close-knit family of friends, artists, and pastors who dramatically shape the songs that accompany our worship. Recently, I have been noticing more and more connections within my life and the lives of those around me — the joy, pain, sorrow or rebirth that draws us nearer to God and to one another. How does the divine composer weave together our imperfect songs and actions into the brilliant fabric of lives restored, redeemed?

Improvisation

Improvisation, which is essential to jazz, opens to us a process mirroring God’s work on earth. Walking amidst trials on my own journey, my spirit fills with new songs as life springs up around me. Here is enough inspiration for a lifetime of creative responses. Whenever we recognize that our song is a gift it relieves us of the burden of self-reliance and encourages openness to grace and connection with others. As we listen more intently, we let go of our agendas and fears, heightening our awareness of the presence of the Holy Spirit in our community. Silence clears our head and heart, opening space for God to take root in our imaginations. Attention to the quiet, still voice in our midst promotes harmony among those gathered for worship and an awareness of our personal and communal role in the larger world. The process of self-realization and relationship to those around us requires deep listening, which is the essence of improvisation.

One of my teachers speaks of “finding” a song rather than composing it. I admire this attitude and have found it to be true in my own practice. I play musical ideas over and over again until something speaks to me. I recall a scripture verse from my childhood: “Ask, and it will be given you; seek, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you.”[1] To anyone who searches for a way to practice improvisation, a simple method for approaching this art form is revealed in these words: Ask. Seek. Knock.

A Simple Method

ASK When we ask for guidance and courage to take the next step into the unknown territory of improvisation, we ready ourselves to step into the musical moment, clearing our mind of anything preordained. Improvisation asks for increased trust among the congregation and fellow musicians, since anything new requires patience and cooperation. Asking can be a communal process: an assembly poses questions to itself about an alternative way to approach music in worship.

Whenever an individual or group moves away from the written page, there will always be a great temptation to return to something that is planned and comfortable. However, jazz artists are defined by their desire to counter this natural impulse, adapting the music as needed for each occasion. Visionary saxophonist Charlie Parker once said, “I realized by using the high notes of the chords as a melodic line, and by the right harmonic progression, I could play what I heard inside me. That’s when I was born.”[2]

SEEK In order to seek the Holy Spirit’s movement through our instruments and voices, we listen carefully, praying that God will work within us. Practicing countless melodic and rhythmic variations, we hope to eventually let go of what is familiar to us and become fluent vehicles for the Spirit in our midst. Improvisation allows for active responses to a baptism, birth, death, or pointed text. Human error and hilarious moments lighten the mood and require quick thinking for our song leaders, bringing everyone closer together and reminding us to not always take our songs too seriously.

I have a fond memory of an improvised psalm setting where the simple refrain “be glad” emerged within the assembly over the course of the piece. After everyone finished playing and singing, my two year-old daughter sang a solo version of the refrain. This moment of childlike faith and innocence led to a church filled with joyous laughter at the impromptu coda.

KNOCK When we courageously put an idea into the world, we are knocking at someone’s door. Our action will have internal and external reactions as the notes that we choose are echoed and countered by our community. I usually find this step a leap of faith and the most difficult one to take. However, once an idea or motive comes forth from our mind and instrument, only listening is required to move forward. We listen as we go, adding musical ideas organically and gluing phrases one to another like building blocks. When others join the conversation, we need to open our ears to these stimuli: text, line, texture, dynamics, harmony, phrase, emotions, and surroundings.

It helps to limit musical choices at the outset to avoid being overwhelmed with options. Deciding on a single mode, rhythmic feel and three- or four-note possibilities facilitates confident language and communication.

Bringing Jazz to Church

Challenges arise when bringing jazz to church. Aural teaching, which is commonly used to introduce new songs to the assembly, has its drawbacks. Text is frequently simplified for ease of repetition, producing truncated phrases and forms. The impact of extended lyrics in printed songs or hymns can be lost. In addition, jazz can sometimes instill fear of the unknown or the feeling of a members-only club to which only the performers are invited or welcome. In a quest for deeper, more authentic artistry and communion with God, some musicians have turned inward, unearthing extended, prayerful musical meditations. This movement raises questions however. How can we relate improvising techniques to the whole church and not just the musicians leading worship? Can the church open its doors to these artists and their songs without disrupting a sense of flow, mood, or intended focus within the liturgy?

Although these challenges are real, jazz also offers brilliant gifts to the church. Reflecting Christ’s vulnerability and forgiveness, this art form embraces our faults and relates to us, regardless of where we are on our spiritual path. The wealth of texts, hymns, and songs that the church already possesses informs new styles and ideas that can be developed uniquely for each congregation and generation. In the jazz ministry at Saint Peter’s we encourage congregants to participate in singing, or even speaking, a psalm or prayer with improvised accompaniment. We have asked ourselves how traditional elements might be re-imagined in a modern context, employing innovative harmonies or rhythms from our culture and from others around the world. The result has been a creative and ongoing process.

One of our song leaders, Melissa Stylianou, described her Sunday experiences at our church in this way:

Jazz Vespers is the musical highlight of what can be a totally crazy week filled with teaching, my own shows, all that commuting, other “side man” gigs, and the delights of being a new mother. I know when I come here, I’ll be challenged by the compositions, and challenged by the freedom that Ike gives us: the license, and even the imperative, to create something in the moment that really means something to us and that is communicated to (and sometimes sung by) the congregation. The freedom of not knowing what is coming next is sometimes uncomfortable for me, but I’m always amazed at how this large group can work together in the moment like one organism…. One of the things that stuck with me from my theater school days, and which I draw upon all the time when singing this music is something a teacher said to us one day: “Be Here Now.” It’s harder than it sounds and takes constant vigilance, but it really does make a difference in making music (and in life in general), and I feel like it’s an apt explanation for why this band can do what it does: we’re all working hard at Being Here Now.

A rendition of Psalm 37 was recently completely improvised at our jazz vespers with members of our band, Evergreen. A dancer from our community, Hannah Barnard, joined us in a free dance response to the text and music. The psalmist proclaims, “Commit your way to the LORD; put your trust in the LORD and see what God will do.” The approach for many of our jazz liturgies involves giving musicians the psalm text with no written music or chords. In this case, our guitarist, Jesse Lewis, begins improvising with no instructions or limitations, using only the words and the service context as his guide. Once a drone or harmonic foundation is established along with vibraphonist Chris Dingman, singers Melissa Stylianou and Chanda Rule knit together words and melodies. As the refrain is developed in the moment, it is repeated and shared aurally with the congregation. The singers may introduce multiple refrains, rounds or harmony parts, but in this example a simple phrase is echoed in the middle and at the end of the piece. The ensemble accompanies, using only their ears and experience, building trust and friendship based on constantly watching out for each other and elevating the whole body above a single part. Church members and visitors are welcome to join in singing, regardless of age, note-reading ability, or language skills.

PSALM 37 Improvisation

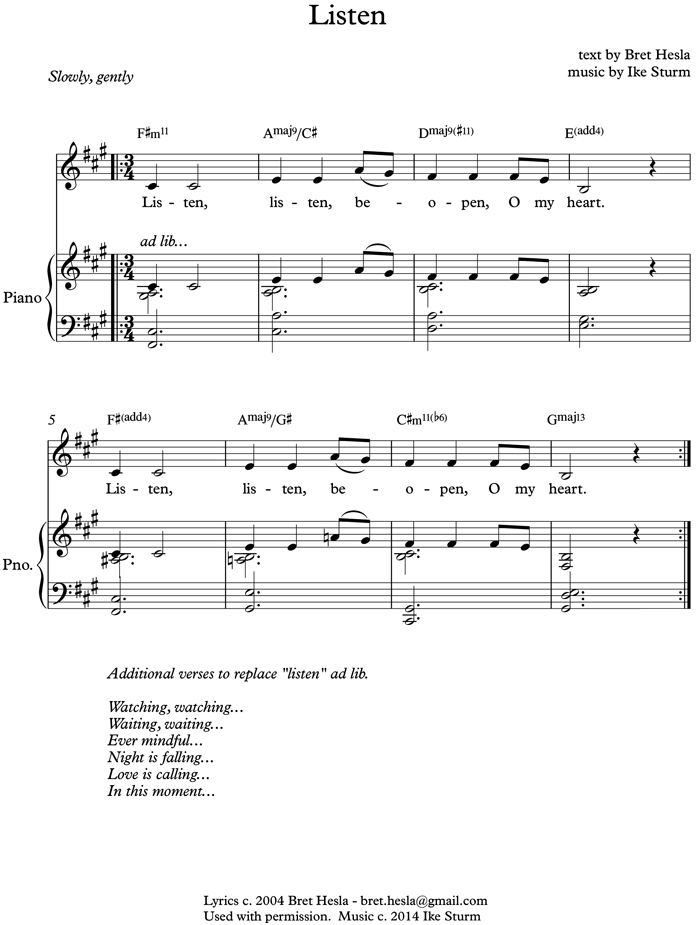

This past Lenten season our song leaders taught a song called “Listen” each week to the congregation. The song allowed the assembly and guest musicians to sing and play without any printed music while lighting candles, offering prayers, and moving throughout the sanctuary. Using this simple “lead sheet” format also allowed adaptation for diverse musical groups to participate in the song throughout the Sundays of Lent. These included a cappella singing, a jazz/gospel quartet, a chamber ensemble of strings, and a big band.

The following video shows my wife, the singer Misty Ann Sturm, leading us in our setting of Psalm 23. This piece contains a mix of fully notated chamber parts with improvisation integrated into the saxophone, guitar, bass, and drums. “Restores my soul” emerges as a refrain that we teach to the congregation. Even within the rhythmic context of an odd meter, having the song leader model the line confidently alone, then welcoming participation with repetitions of the refrain, helps the assembly to learn comfortably and immediately. With a cappella singing, this technique allows for flexibility in form and duration and often leads to meditative repetitions beyond the written form.

Conclusion

As I look back over several years’ experience of creating original songs, I see a strong common thread woven through them all: the theme of restoration. In retrospect, the work of the Spirit becomes evident in ways that even I was not aware of at the time. I am learning that my personal musical statements speak out long before I understand what is actually happening in my spirit.

During these years, my father has battled cancer and he has recently passed away. His journey has been defined by unbelievable strength and perseverance. The challenges involved have called out love and faith from him and those around him. A collection of songs about renewal has grown out of this season in my life, with the help of some of my closest friends and family. The project is called Shelter of Trees, the title being drawn from a text written by my friend Cheryl Mitchell. A line from her beautiful poem became our refrain: “Close your eyes and be, and you will be with me.”

Shelter of Trees

Ike Sturm is a bassist, composer and teacher, serving as Music Director for the Jazz Ministry at Saint Peter’s Church in New York City. Ike and his ensemble, Evergreen, frequently create and perform original music for liturgies at Saint Peter’s and gatherings around the world.

Ike Sturm is a bassist, composer and teacher, serving as Music Director for the Jazz Ministry at Saint Peter’s Church in New York City. Ike and his ensemble, Evergreen, frequently create and perform original music for liturgies at Saint Peter’s and gatherings around the world.

www.saintpeters.org

www.ikesturm.com

FOOTNOTES

[1] Matthew 7:7.

[2] Charlie Parker, quoted in The Words of African-American Heroes, ed. Clara Villarosa, New York: Newmarket Press, 2011, p. 13.

____

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Recommended Citation: Sturm, Ike (2014) “Listen,” The Yale ISM Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 14.

Available at: https://ismreview.yale.edu/