Valarie Lee James

Story cloth embroidered by Wendy, Asylum-seeker from El Salvador, 2020

We enter into the art of immigration through the wide-open eye, a symbol of watchful witness found in the artwork of migrating youth. Like children’s drawings smuggled out of Nazi concentration camps that incriminated Auschwitz personnel, or the detailed drawings by refugee children from Darfur that bore witness to their country’s 2003 genocide, recent drawings by migrant children locked in detention facilities on the U.S. southern border show that the wide-open eyes of children never forget. Through their enduring witness, neither shall we.

Eye of Witness: The Art of Asylum

Drawn by youth at Casa Alitas Migrant Shelter, Tucson, AZ 2019

Casa Alitas is Tucson’s main short-term migrant shelter for people coming from Mexico, Central and South America. From 2018-2019, guests at Casa Alitas would often draw the unvarnished truth of migration at night after shelter volunteers had left for the day. With chunks of crayon and chalk, both children and adults drew with abandon on scraps of paper, ripped cardboard, or whatever was at hand. They used bits of harvested tape and even gum to attach their drawings to the wall, ensuring that their drawings would be seen by volunteers in the morning so they would know the truth of what they had been through.

Within the refugee community, where most every guest has been traumatized and verbal communication can be challenging, the need for the universal language of art is profound.

As the volunteer Arts Coordinator at the shelter, I remember a young boy who, while standing up at a table, rapidly drew house after house, filling up the entire piece of paper as soon as I laid it before him. It was all I could do to keep up with him as I brought in bin after bin of crayons, colored pencils, markers. After his third house, his breathing slowed, his drawing was more fluid, and he finally sat down.

It is in the safe retelling of our stories through expressive arts – visual arts, storytelling, movement, and music – that we begin to loosen the grip of trauma upon our bodies and brains, our hearts, and our souls. Healing happens in the creation of narrative and meaning. Trauma-informed arts and activities provide calm in the storm, allow for safe self-expression, and promote resilience.

Most guests, then and now, stay at the shelter for just a few days, until they are able to arrange transportation to families and sponsors across the United States. In a short-term facility like Casa Alitas, arts facilitators gently host groups, provide a choice of art materials, encourage and facilitate. Careful not to re-traumatize, they do not prompt or elicit intimate personal stories from guests.

From 2018-2019, during an expanded influx of asylum-seekers from Mexico, Central and South America, so much art was produced at the shelter that it soon became an exhibition. Many of the drawings and paintings chosen for the exhibit were pulled from stacks of paper discovered after guests had left. These visual testimonies, often anonymous, are unsparingly honest and authentic.

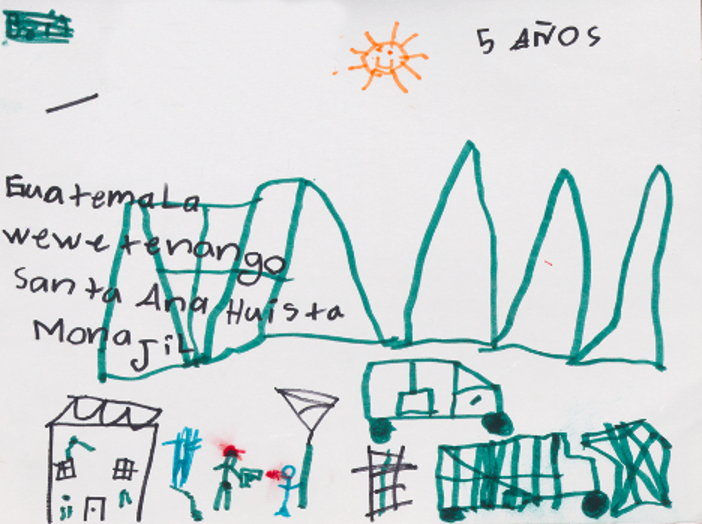

In the exhibition “Hope and Healing: The Art of Asylum,” one small, easily overlooked drawing is stark testimony of a five-year old’s direct experience of trauma. In the foreground, two stick figures locked in a gun fight stand next to a house riddled with what appears to be gunshot holes. The weapon looms large in the foreground. Both figures’ heads are smudged with blood red marker.

Drawn by a child at Casa Alitas Shelter, Tucson, Arizona, 2019

To the right, a door-shaped grid of criss-crossed bars drawn with black marker is strikingly similar to other drawings by children in detention. Next to the grid, two large green trucks head straight for a larger fortified wall, another oft-seen symbol in drawings by children crossing the border. In the background we see a barrier of spiky shapes–- mountains, or perhaps a wall, we do not know. We will never really know, nor can we presume to analyze what has happened to this child. We can only acknowledge and honor what we see.

Art by Selvin, Casa Alitas, Tucson, Arizona 2018

Signs of displacement and dislocation rip through young refugees’ unbridled artwork: volcanos erupting, people and animals fleeing, roads and rivers, walls and vehicle barriers, cars, trains and airplanes, all manner of birds, evidence of human-and climate-caused violence, trauma, and loss.

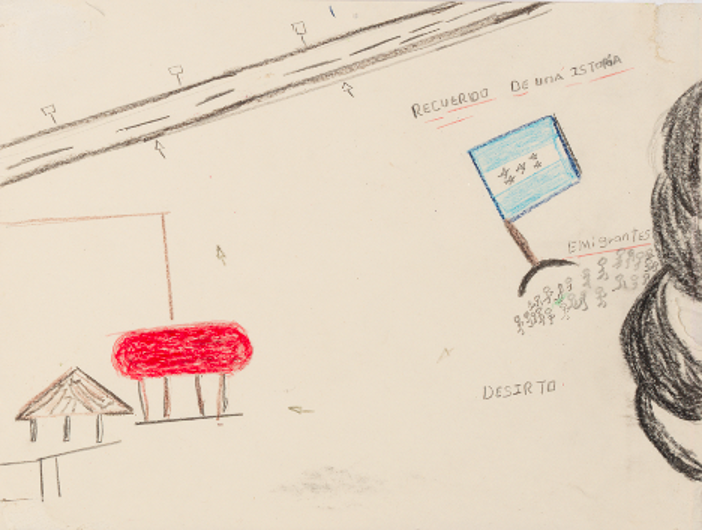

Anonymous, Casa Alitas, Tucson, Arizona 2019

In the piece above, a large group of people flees through the desert from what appears to be rolls of concertina wire. Arrows point to the safety of a highway in the distance. The message: Recuerdo de una historia, “Memory of a story,” beseeches the viewer to remember this story.

For other guests safely on their way to family or sponsors in the U.S., optimism and hope – bright flowers, sunshine, and smiling faces – characterizes their artwork.

A popular prompt to “Draw what you love” (or, “draw what’s in your heart”) elicits calm and generates a sense of safety for traumatized children and adults. This simple, affirming prompt with a choice of art materials (including embroidery and other culturally aligned textile arts), allows guests to create whatever they need to feel more grounded while in the throes of migration. Drawing what you love became a cornerstone practice of all trauma-informed arts and activities programs at the shelter.

On rare occasions, the prompt might lead a guest to draw subject matter that represents what they’ve loved and lost, especially youth who, in the chaos, are sometimes forced to leave beloved pets behind. Not wanting to burden their parents, they often keep their feelings of loss to themselves. The act of drawing the pets they love became an exercise in remembering and honoring. When finished, they were quick to proudly share stories of their beloved pets with the other kids and volunteers.

Artwork by adults and children brimming with faith and gratitude, churches, crosses, and devotional figures, were often the first (sometimes only) images and symbols completed by guests. Border Patrol and I.C.E. regularly take away all personal items from people when they’re apprehended, but they cannot take away one’s faith.

Cristian y Jadiel, Casa Alitas, Tucson, Arizona, 2019

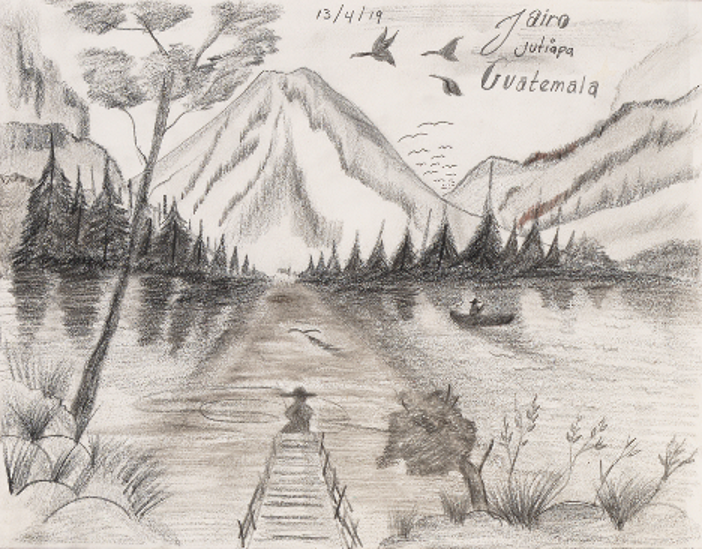

Other images grounded in faith, drawn instinctively by guests, are bucolic landscapes coupled with messages of thanks and gratitude to God and the volunteers.

Drawn by Jairo, Casa Alitas, Tucson, Arizona, 2019

In addition to the violence that stalks our nearest neighbors and forces them to leave their homelands, many are climate refugees. Illustrating healthy harvests and remembering el mundo natural and healthy flora and fauna is a devotional act that keeps hope alive.

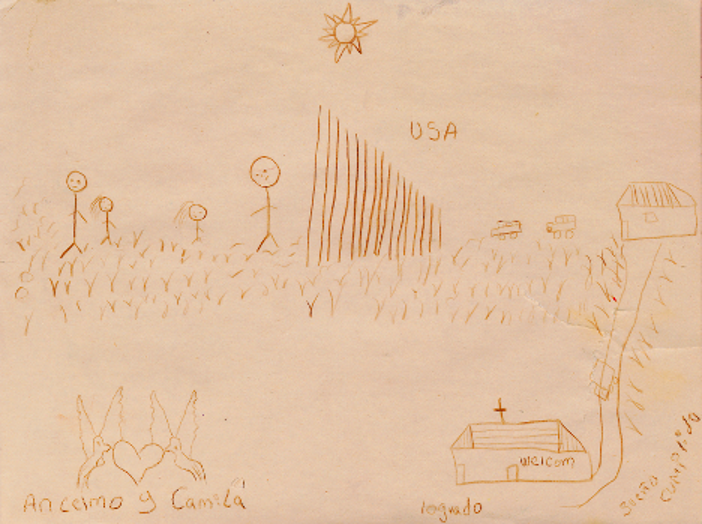

Anonymous, Casa Alitas, Tucson, Arizona 2019

In the image above, rendered in a faint hand, a family is stuck on one side of a looming wall while on the other side, we see a church with the word “Welcome” in English and the words “Logrado – Accomplished” and “Sueno Complido – the Dream Complete.” This narrative drawing is similar to storied images seen in retablos, religious paintings (specifically ex-votos)– small, personal, stylistically primitive votive paintings that were historically given to churches to fulfill a vow. Ex-votos are visual prayers of gratitude and devotion to God for having overcome a terrible ordeal: an accident, illness, or a grave loss, or, as in this case, for having made it through the gauntlet of migration to the “promised land.”

In the book Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States,[1] authors Jorge Durand and Douglas S. Massey tell us that retablos address “The human need to communicate with the divine (that) transcends temporal and cultural boundaries. And that… the practice of leaving of objects to supplicate or thank a deity has very ancient roots.”

Hand of Faith: Embroidered Retablos at the Border

Complete story cloth embroidered by Wendy, asylum-seeker from El Salvador, 2020

In the Fall of 2020, Wendy, a devout Salvadorian mother seeking asylum, embroidered the story cloth above that is the centerpiece of “Bordando Esperanza, or Embroidering Hope: Devotional Retablos of Asylum” (2020-2021). It is a group exhibition of embroideries created by asylum-seekers stranded at the U.S.-Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After almost a year on the streets and in shelters in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, “searching for the American Dream,” Wendy had no choice but to return to El Salvador. On a layover at the Guatemalan border, she stitched this ex-voto-like embroidery-bordado.

Wendy is the former on-site coordinator of Artisans Beyond Borders, our bi-national Border Arts ministry for Asylum-seekers in Nogales, Sonora. She adds this visual memoir, her recuerdo, to the exhibit because she wants the world to understand her experience and the faith she’s leaned on against insurmountable odds. Similar to story cloths from other conflict areas around the world, Wendy’s personal narrative in needle and thread documents, and also begins to heal, the trauma of migration. Like a traditional ex-voto, she leaves it now, in supplication and thanks, at the capilla, the chapel of the exhibit, to join other devotional retablos embroidered by her compañeras.

Wendy’s story cloth blends her lived experience, pictured on one side of the embroidered border wall, with the imagined, pictured on the other side. In the upper left, we first see her hopes: the shining city on the hill, the sign that reads EEUU (Estados Unidos – United States), and the migrant with his back towards us, cell phone in his pocket.

In the upper middle, a man with a gun assaults a woman and child. The figures represent Wendy’s greatest fear: being assaulted on the road with her two-year-old son. She shared the crushing nightmares she had after her shelter-mate in Nogales, another young mother of two, whispered about passing dead bodies in the Sonoran Desert as she crossed the border on foot with her two children to join her husband and the rest of her family in the U.S.

In these two elements alone – the migrant gazing off into the shining city on the hill and the woman and her child being assaulted, we see the inexorable relationship between hope and fear.

In the upper right corner: the great wide-open eye sheds its tear into a satchel of sorrow tied to a migrant’s staff. Behind the traveler are crosses and headstones and water bottles littered across the desert. Ahead we see a bare, black tree and omnipresent black birds. Death stalks the man as he walks off the edge of the cloth and into the unknown.

As our eyes travel down to the lower right, we see the ubiquitous Golden Arches. Wendy and her friends at the shelter could see McDonald’s el otra lado, on the other side through the fence every day. They swore to meet there when they made it across.

The gaping maw of the border wall topped with rolled razor wire snakes through Wendy’s world. With needle and thread, she artfully stitched in the man she watched one day trying to scale the wall and pantalones left behind, caught on the wire. We wonder, did he make it across?

On the Mexican side of the wall, the train – la Bestia, replete with tiny figures riding on top, slams into the wall, going nowhere fast. Next to the train, we see a small medicinal portion of hope: helpful frontline workers represented by the ambulance that she says helped save her son’s life when he suddenly fell ill. Next to the ambulance is a table topped with balls of color. A facilitator from Artisans Beyond Borders passes out embroidery supplies, art therapy that would prove to be indispensable during the long wait at the hospital by her son’s side.

The three figures above are the family Wendy had with her in Nogales; her mother and her younger sister, and the others are friends watching and waiting for the border to open.

In the bottom left corner of the cloth Wendy holds onto her son Johnny’s hand, as she walks the streets of Nogales in winter with no place to rest, bent over with the weight of her suitcase, and her two-year-old. She tells me that this is what she remembers the most, the weight bearing down on her, so heavy that sometimes she felt she couldn’t breathe.

Early on into the pandemic, an increasing number of embroidered devotional retablos came in from the shelters and off of the streets. Much of this work is deeply personal but when offered back to them with love, the artisans refuse. They would rather their work be homed with supporters in the U.S.

“If it infects me lord, let it be with your faith and love,” Original retablo embroidered by Irma from Guatemala, U.S. – Mexico border, 2020

Whether they’ve embroidered conventional Christian iconography or elements of the natural world infused with Dios, the artisan’s devotional retablos rendered in cloth are intimate personal prayers, embodied testimonies of faith.

For most of the asylum-seekers, the act of devotion lies in material practice, the mindful stitching itself, the slow contemplative act of moving a needle and thread through cloth. The act of embroidering their original designs inspired by the natural world and memories of home permeates the soul and body with peace. The clean cloth canvas secured within the embroidery hoop allows the maker to begin the process of mending a life that has been ripped and torn asunder. The artisan has the agency to design a world, even a heaven, of his or her own.

“I leave my destiny in your hands my God,” Original retablo embroidered by Dalianas from Cuba, U.S.- Mexico border, 2020.

Unlike the mothers (and some fathers) at Casa Alitas who worked with embroidery materials during their brief stay and left for their new homes carrying works in progress, most of the bordadoras in the Artisans Beyond Borders collective have been stranded at the U.S.-Mexico port of entry for over a year now. Time weighs heavy on their hands and their craft deepens as they surrender to each passing day. In addition to the small but essential wage they receive for their handwork – a huge blessing for families with so little – the venerable art of embroidery, uniquely suited to trauma care, reminds us that the power of God’s grace is at our fingertips.

When Wendy completed her story cloth, she was exhausted but relieved. “The weight has been lifted off my shoulders at last,” she said. “I have told my story.”

“The name of the Lord is strength,” Original retablo embroidered by Felicitas, U.S.- Mexico border 2020

Valarie Lee James

Valarie Lee James is a longtime resident of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands and founder of Artisans Beyond Borders. A former Clinical Art Therapist, she was coordinator of the all-volunteer Trauma-informed Arts & Activities Program at Tucson’s Casa Alitas Migrant shelter, and co-curator of “Hope & Healing: The Art of Asylum” exhibition of artwork by Casa Alitas refugee youth. Her writings on arts and immigration can be found at America Magazine, Open Democracy, and EpiscopalMigrationMinistries.org, and as a Benedictine Oblate, she writes at The Global Sisters Report. Artisans’ “Profiles in Courage and Creativity” can be read at Art and Faith in the Desert.

- Website: ArtisansBeyondBorders.org

- FB: https://www.facebook.com/BordandoEsperanzaSinFronteras/

- IG: artisansbeyondborders

[1]Jorge Durand and Douglas S. Massey, Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States, (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995), 9.